Month before standoff, China blocked 5 patrol points in Depsang

Defence Minister Rajnath Singh, making a statement in Rajya Sabha Thursday on the situation along the Line of Actual Control in Ladakh, said “patrolling patterns are traditional and well-defined… no force on earth can stop our soldiers from patrolling” and “there will be no change in the patrolling pattern”.

But the situation on the ground, especially in the Depsang Plains in the far north of Ladakh, is very different. Because more than a month before the standoff began in May on the north bank of Pangong Tso where Indian soldiers are not being allowed to move beyond Finger 4 to the LAC point at Finger 8, Chinese troops cut off Indian access to five “traditional” patrolling points (PPs) in the Depsang Plains.

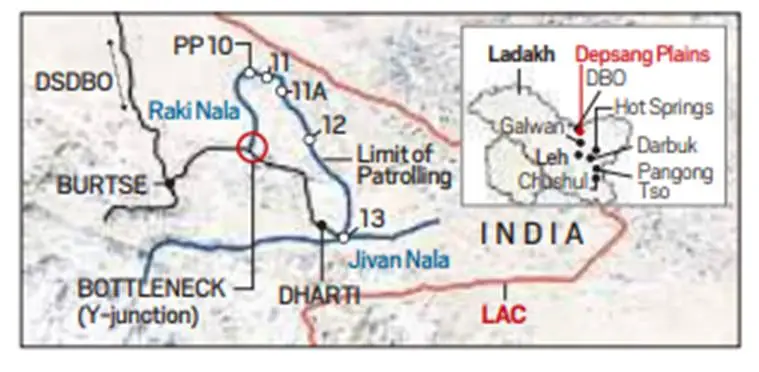

Confirming this, a top source in the government told The Sunday Express earlier this week that the Chinese blocked access to PPs 10, 11, 11A, 12 and 13 in March-April this year.

Located east of the strategic Sub-Sector North road or the Darbuk-Shyok-Daulat Beg Oldie (DSDBO) road, the five PPs are close to the LAC, but not at the LAC itself – in short, they are located well inside the line that marks Indian territory. While the government source played down the extent of the area where Indian troops are being denied access, estimating it to be around 50 sq km or thereabouts, a former member of the China Study Group, the government’s main advisory body that also decides on the location of these patrolling points, said “it is a material change” due to the “tactical and strategic significance” of the area.

The PPs are located east of Bottleneck, a rocky outcrop that provides connectivity across the Depsang Plains. It is about 7 km east of Burtse which is on the DSDBO road and has an Indian Army base.

The track going east from Burtse forks into two at Bottleneck, the reason why it is also called Y-Junction. The track north, following the Raki Nala, goes towards PP10, while the track southeast goes towards PP-13 along Jivan Nala. On the patrolling route moving south, in a rough crescent from PP10 to PP 13, are PPs 11, 11A and 12.

Not having access to these PPs means that the Chinese soldiers are blocking Indians from reaching and asserting control over an area which, according to India, is on its side of the LAC.

By definition, the LAC is the line that defines territory under India’s control. The PPs are meant to be reached to demonstrate that the area in between these points and the LAC can be accessed.

In order to block Indian troops at Bottleneck and deny them access to traditional patrolling routes, the PLA would not only have crossed the LAC, but even the PPs.

According to the government source, Chinese soldiers have not “settled down” at the PPs, but they come and block Indian troops when they go there. The source said Indian troops, if they so wish, can still reach the patrolling points, but that will mean creating another “flashpoint”.

But a former Army commander, who served in the sector, said it is not possible for the Chinese to block Indian troops at Bottleneck unless they have dug in close to the Y-Junction with a sustained surveillance arrangement in place.

In Army parlance, the patrolling points within the LAC, and the traditional routes joining them, are known as “limits of patrolling”. The five patrolling points and the patrol lines joining them form the “limits of patrolling” in Depsang. Some Army officers also refer to these as the “LAC within the LAC”.

The former commander said the limit of patrolling is viewed as the actual LAC since troops are “not mandated” to go beyond these points.

But according to those familiar with India-China issues and aware of the PPs and how and why these were set up within the LAC, these are not meant to be “limits of patrolling”, but “lines of patrolling”. Depending on the terrain, there could be several patrolling routes between the same points, to be decided by the commanders on the ground.

The PPs were set up in the 1970s by the China Study Group, constituted in 1975, comprising top officials from the ministries of Home, Defence, External Affairs, and intelligence agencies in consultation with armed forces and the ITBP. The patrolling points were started in the 1970s before India officially accepted the LAC in 1993.

Former National Security Advisor Shivshankar Menon, in his book Choices: Inside the Making of India’s Foreign Policy, recalled: “In 1976, on the basis of the much better information regarding the border available to India, the Cabinet Committee for Political Affairs established the China Study Group under the foreign secretary to recommend revised patrolling limits, rules of engagement, and the pattern of Indian presence along the border with China”. He noted: “Throughout this period each side slowly moved up to the line, asserting presence through periodic patrols in an intricate pattern that crisscrossed in areas where both states had different interpretations of where the LAC was.”

With the limited infrastructure of that era, the rationale for the patrol points was to make optimum use of men and material, as it was impossible to deploy soldiers to man every inch of the 3,488-km LAC.

As infrastructure gradually improved, the patrolling points were revised from time to time, to India’s advantage. In most places, PPs are now located at the LAC or very close to it. Depsang is one of those areas where the PPs are well inside the LAC.

In Depsang too, a former official said, the PPs have been revised several times since the 1970s, each time moving forward towards the LAC.

As for the area between the LoP (limits/lines of patrolling) and the LAC, former officials said this was not meant to be assumed as given up. Rather, the idea behind developing infrastructure in these areas was to increase the patrolling and extend it further up to the LAC.

Earlier this week, the government source said India has had no access to the areas beyond the LoP for “more than 10 to 15 years”. He said a total area of 972 sq km was now out of Indian access. But others suggest that India has not accessed the area since much earlier, as troops have stuck to routes between the patrolling points.

Former Army commanders suggested that these patrolling points were a more realistic assessment of the areas till where India could assert control.

Control over Depsang Plains is vital to the defence of Ladakh, as it straddles the recently completed DSDBO road, an all-weather supply line from Leh to the final SSN outpost at Daulat Beg Oldie, located near the base of the Karakoram Pass that separates China’s Xinjiang Autonomous Region from Ladakh.

The presence of Chinese soldiers on the Indian side of the LAC could pose a threat to the DSDBO road and areas to its west. On their side of the LAC, the Chinese have built highway G219 from Tibet to Xinjiang, troubled provinces both, through Aksai Chin. They view India’s DSDBO road and the revival of the airstrip at Daulat Beg Oldie as direct threats to G219.

The Depsang Plains are relatively flat, and provide one of the few launchpads for a military offensive in Ladakh. The PLA, according to the government source, has stationed two brigades on its side of the LAC in this region. India has also stationed “more than a brigade” in the area.

Indian express