Leh at the end of the tunnel

Ram Chand was 10 when a harsh winter struck his home in Khoksar, 3,140 metres above the sea, and the coldest inhabited place in Himachal Pradesh’s Lahaul, with temperatures known to hit -30 degrees Celsius. It covered the valley under 13 feet of snow, leaving his family stranded, without much essentials. For a month, Chand’s family survived on boiled potatoes and broth, breaking down their wooden possessions for fuel.

When the weather finally cleared, they started walking, leaving behind their dead livestock. After walking uphill 20 km towards Rohtang Pass, they spent the next night in a cave before making it to Kothi village, the first human settlement on the Kullu side. They finally returned home only in May, when the snow had cleared.

That was in 1957, when only mule tracks connected Khoksar to Manali, a distance of 75 km, via Rohtang Pass, or to the district headquarters Keylong, 45 km north on the Manali-Leh route. Around 1970, a motorable road was built on the Pass, located at a height of nearly 4,000 metres, by the Border Roads Organisation (BRO), offering the people of Lahaul and Spiti (then separate districts, now one) connectivity in the non-winter months (May to September) to the rest of Himachal Pradesh.

Chand is 74 now, a grandfather to seven. Their family still migrates to Kullu during the winters, like other residents of Lahaul-Spiti, now in a bus or their jeep. Many people in Lahaul keep an alternate home in Kullu for the winters. “Only one or two members from a family stay back,” Chand says.

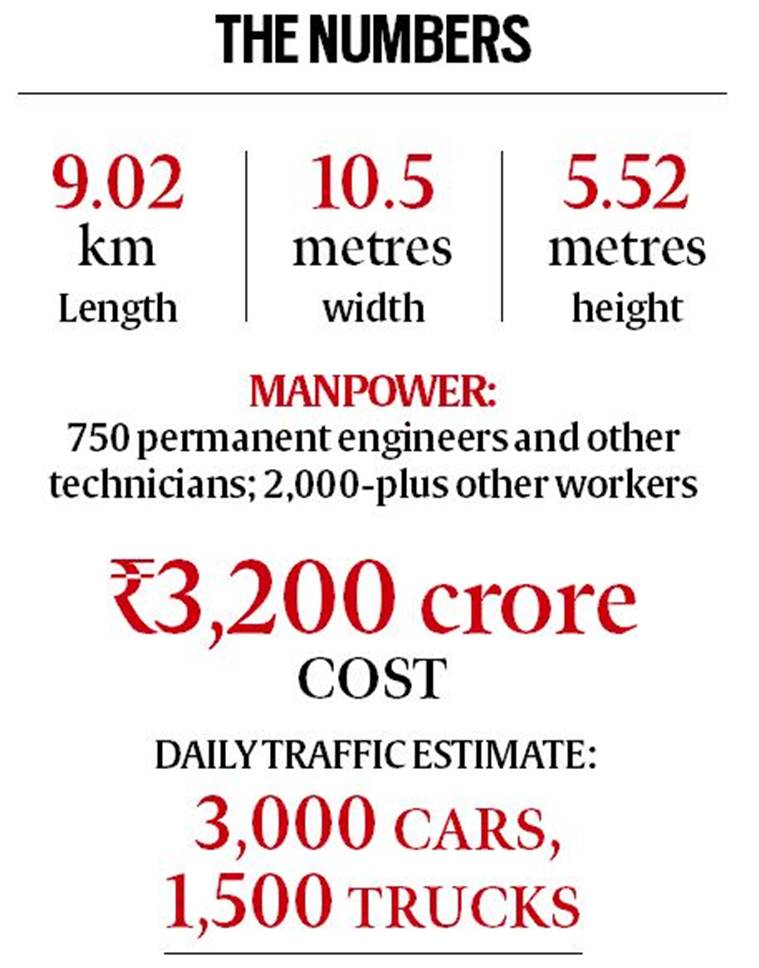

However, days from now, Chand, a farmer, may finally be able to put that nightmarish month of six decades ago behind him. Towards end September, Prime Minister Narendra Modi will inaugurate a tunnel, nearly 40 years in conception, and 10 years and Rs 3,200 crore in the making — its progress slow due as much to the terrain of the eastern Pir Panjal range as bureaucratic delays — thus ensuring that the Lahaul valley won’t remain cut off for more than six months of the year from the world.

Spiti, lying beyond the Kunzum Pass (4,551 m), will still remain inaccessible in the winters.

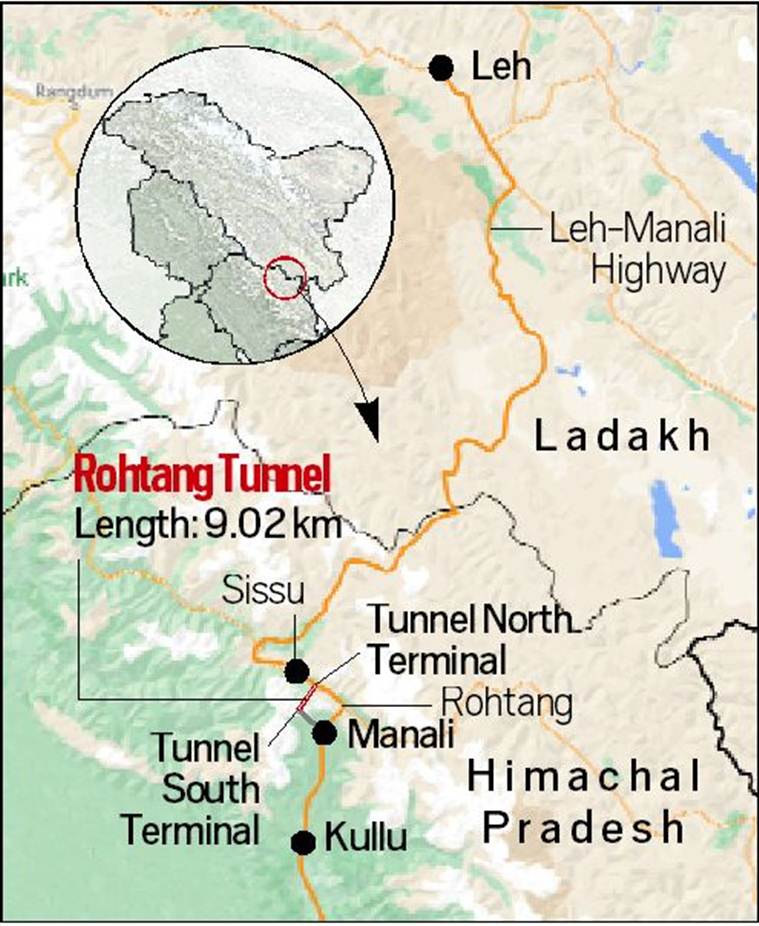

The 9.02-km-long ‘Atal Tunnel’, named by the Modi government after former PM Atal Bihari Vajpayee, is one of the longest road tunnels in the country and, as per the BRO, “the longest highway tunnel above 3,000 metres in the world”. Scheduled to be inaugurated in May, its deadline had to be pushed due to Covid-19.

Cutting through a mountain to the west of Rohtang La, the tunnel will shorten the distance between Solang Valley near Manali to Sissu in Lahaul, the two points it connects, by around 46 km. If driving up to the Pass now takes two-three hours, vehicles will be able to cross the tunnel in 15 minutes.

The project is even more significant due to the rising tensions on the eastern front with China. Since May this year, the procession of Army trucks through the Rohtang Pass has been almost ceaseless, as men and material are ferried to the flash points in Ladakh. Not only does the tunnel mean quicker supplies, but also that Army convoys are no longer hostage to the vagaries of nature and snowfall.

“Yes, snowfall can still block the three passes further down the road to Leh, but we can try and keep those open. The very fact that we can now move beyond Rohtang without any fear of delay gives us a strategic edge,” says a senior Army officer who did not want to be named.

BRO officials say vehicles can travel up to 80 km per hour inside the tunnel. Up to 1,500 trucks and 3,000 cars are expected to use it daily when the situation gets to normal post Covid-19 restrictions.

As per the BRO, the 9.02-km-long Atal Tunnel “the longest highway tunnel above 3,000 metres in the world”.

As per the BRO, the 9.02-km-long Atal Tunnel “the longest highway tunnel above 3,000 metres in the world”.

Having learnt to live a lifetime on “scarce resources”, Ram Chand expects the tunnel to “make our lives easier”.

Easy is not a word one would readily associate with the district of Lahaul-Spiti, lying in the cold desert region of the western Himalayas and sparsely populated (around 31,500 people spread out over nearly 14,000 sq m). Declared a scheduled area under the Fifth Schedule of the Constitution, entitled to special protections and provisions, the district is almost entirely tribal (81.4%, as per the 2011 Census), with Scheduled Castes forming 7% of the population. The annual tribal sub-plan of the state government covers Lahaul-Spiti.

On the ground, there is little to show for it. With the high mountains to the south acting as a barrier to the monsoon winds, the region is mostly dependent on western disturbances for precipitation. There is no vegetation except grass and shrubs, barring Lahaul’s alpine pastures. Agriculture remains the main occupation, with major crops being potatoes, peas, cauliflower and, now, broccoli and iceberg lettuce. In recent decades, with rising temperatures shifting apple-producing areas to higher altitudes, apples too are cultivated in parts of the district.

The Rohtang Pass provides a gateway to the resource-rich Kullu, when it is not snowed under. People here associate the months October to April with prolonged disruption of essential services, with the low temperatures also affecting power and mobile phone lines.

BSNL landline phones have not worked in the district for several years now. There are around 20-25 mobile towers in Lahaul, and three-four in Spiti. 4G services are available, but Internet speed remains low and erratic.

The limited health services are further curtailed in winters, and the seriously ill have to be airlifted out — if the weather allows it. In January, for instance, a helicopter carrying a patient from Keylong to Kullu was forced to retreat due to adverse conditions.

A timeline of Atal Tunnel at Rohtang Pass.

A timeline of Atal Tunnel at Rohtang Pass.

“Medical emergencies in winter are common, but people have few options,” says Gyan Chand, 75, who was once airlifted from Sissu to a hospital in Kullu after he fractured his leg.

Keylong has a civil hospital, but lack of specialist doctors has been a long-standing complaint of residents. Chief Medical Officer Dr Paljor says there is one regional hospital, 17 primary health centres, three community health centres and 37 sub-centres in the district. However, he admits, while the Lahaul sub-division has 34 doctors, there’s no specialist.

While Lahaul-Spiti has a college, teachers from other areas are reluctant to serve in the district. Students mostly go to institutions in Kullu, or Shimla and Chandigarh. During the Covid pandemic, there has been very little virtual learning, due to no or erratic Internet connectivity. Teachers have been giving offline assignments and worksheets to students.

Dharam Chand, 81, from Teling village, which lies close to the northern portal of the Atal Tunnel, says once Manali is more accessible, the bus fare will be cheaper. “This will benefit the farmers here who take their produce to Manali and other places to sell.” Dharam Chand grows potatoes and cauliflowers.

Om Prakash Thakur from Gojra village in Manali, employed in the security team at the tunnel site, says it has also provided people like him an alternative employment opportunity. “I was unable to find work during the pandemic and joined here recently,” says a resident of Bhuntar in Kullu deployed at a security barrier near the southern portal.

Khoksar village of around 100 people, which almost empties out in winter as supplies run scarce.

Khoksar village of around 100 people, which almost empties out in winter as supplies run scarce.

The first feasibility study of the Rohtang tunnel was carried out between 1983-85, by the Geological Survey of India, followed by another by RITES in 1990. In July 2010, the foundation stone was laid by UPA chairperson Sonia Gandhi. The first deadline was February 2015, but the project got repeatedly delayed due to problems such as geography of the area, seepage from a brook, and finally Covid-19.

Workers, vehicles etc are giving finishing touches at both the south and north portals.

There are around 750 engineers and permanent technicians, besides more than 2,000 workers deployed at the site, including for security. Cement is carted all the way from a factory in Solan, more than 200 km away, while other material such as steel, electrical equipment etc has been brought from multiple sources, in Delhi, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Faridabad etc.

One of the major challenges was working in the sub-zero temperatures, requiring special gear. There is a permanent doctor at the site, with the closest hospital in Manali, around 20 km away. A helipad has been created near the northern portal for emergency services. Electronic chips have been issued to workers for rescue in case of avalanches etc.

“Not a single casualty has been reported during construction work in all these years,” says a BRO official, refusing to be identified.

The other challenge was cutting a tunnel through the mountain, which is made of rocks with a number of minor faults and at least one major fault charged with water, as well as brittle rocks towards the northern portal.

The Seri Nullah fault, 587 metres long, caused the maximum delay. In 2011, ingress was noticed towards the top of the tunnel from the nullah, at 140 litres per second. Waterproofing was used to control the seepage, but the process took about five years.

Earlier this year, the final challenge was thrown by the lockdown. Work stopped at the site as labourers left for their homes and the supply of material was hit.

The BRO official says, “The first two weeks (after the lockdown) were spent seeking permissions across multiple states to allow the supply chains to resume. Gradually, the labourers returned, with a majority of them from within Himachal.”

Care has been taken since to ensure that all Covid precautions are strictly followed. “Not a single infection has been reported from the site till date,” the official says. Himachal has more than 6,800 Covid-19 cases.

Illumination: Auto adjusts as per light conditions outside for visual adaptation and energy saving.

Illumination: Auto adjusts as per light conditions outside for visual adaptation and energy saving.

The Atal Tunnel is one of the most challenging projects undertaken by the BRO, which develops and maintains road networks in India’s border areas, around 33,000 km length of it, and has Army officers on deputation among its ranks.

The tunnel boasts features such as a telephone facility every 150 metres, fire hydrant every 60 metres, emergency exit every 500 metres, turning cavern every 2.2 km (to allow U-turns and parking if a vehicle breaks down), air quality monitoring facility every 1 km, broadcasting system and automatic incident detection system every 250 metres. It also has an emergency escape tunnel underneath — as per the BRO, a first in India, as escape tunnels are usually built alongside main tunnels.

Up ahead, the BRO has on its table at least three more tunnels on the Manali-Leh route and one tunnel on an alternative route being developed on Darcha-Padam-Nimu axis, to ensure full all-weather connectivity to Ladakh.

A BRO official says a detailed project report has been prepared for the 13.2-km-long tunnel required at Baralacha La, located at a height of 4,880 metres. “Another 14.78-km tunnel is required at Lachung La at 5,100 metres, while Tanglang La, at 5,320 metres, will need a 7.32-km tunnel… Unlike the Atal Tunnel, it will be difficult to maintain camps at these locations.”

Prime Minister Narendra Modi is expected to inaugurate the Atal Tunnel at Rohtang late September.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi is expected to inaugurate the Atal Tunnel at Rohtang late September.

Lahaul-Spiti Deputy Commissioner Kamal Kant Saroch is hoping the tunnel will open up the region, much like Ladakh, to tourism. “I have seen the Himalayas till Bhutan but nowhere else have I found such uniquely glaciated and beautiful mountains. There’s a new glacier at every turn,” he points out.

According to the state tourism department, 1.33 lakh tourists, including 13,764 foreigners, visited Lahaul-Spiti in 2018. Of the state’s 1.64 crore tourists that year, Lahaul-Spiti reported the lowest footfall while neighbouring Kullu clocked the highest (more than 30 lakh). Last year’s data is not available, while this year, there have been negligible tourists.

Mostly, Lahaul is a stopover for travellers en route to Leh or Manali, and the highway passing through is dotted with home-stays, hotels and campsites.

“Traffic jams on the Rohtang sometimes dissuade tourists, but with the tunnel, they can travel through here to Leh easily,” says Saroch.

The district administration too spends the summer months preparing for the snow. According to District Food and Supplies Controller Brijender Singh, around 300 metric tonnes of wheat flour, 220 MT rice, 45 MT pulses, 30 MT sugar and 15 MT salt is usually distributed under the PDS by the onset of winters, to last till March 31. Kerosene is distributed on an annual basis, with the department keeping a reserve stock of 60 to 70 kilolitres for the winters.

“As soon as the roads open in summer, we start bringing the essentials… But resources often have to be rationed due to the lack of regular supply. The situation is expected to improve now, not just due to the tunnel but also because the BRO plans to keep the highway towards Leh clear of snow in the winters,” Saroch says.

A month from now, will be the first test of this resolve. Will Lahaul finally see the end of its long winter?

Explained: Strategic edge

At a time when tensions run high on the eastern front with China, the 9.02-km tunnel whose need has been long felt will ensure that Army convoys won’t hit the 4-km-high blockade in the form of the Rohtang Pass, that is snowed under during winters. It is also a guarantee against the movement of troops or supplies being held hostage to nature.

Indian express